Introduction

Alan Turing created the Turing Test in 1950,1 Marvin Minsky wrote the first neural network in 1951,2 and arguments about whether AI will destroy us all or lead to technological utopia have been around ever since.

In this piece I’ll be talking about two particular bits of rhetoric that have found an apparently unlikely partnership in the past five years. The impending obsolescence of humanity locked eyes across the room with a utopian vision of all-powerful AI that sees to all our needs. They started a forbidden romance that has since enthralled even the most serious tech industry leaders.

I myself was enthralled with the story at first, but more recently I’ve come to believe it may end in tragedy.

Part 1: The Allure of Universal Basic Income

Universal Basic Income as a Proposed Solution to the AI-pocalypse

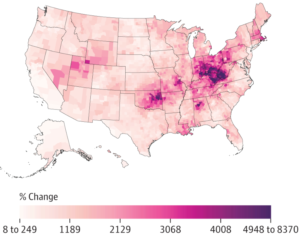

The economic AI-pocalypse is worth more consideration than your average AI doomsday scenario. This version of the AI-pocalypse refers to the simple fact that AI has already displaced many human workers and is projected to do so at an increasing rate. Technological unemployment3 is not a new problem, but the premise of the economic AI-pocalypse is that this time it’s different. The premise is that unlike the industrial revolution, this kind of automation can truly create a world where human labor of all kinds is no longer needed.

Basic income is also an idea with many forms, but Universal Basic Income (UBI) refers to the idea of giving everyone an income sufficient to meet basic needs, with zero conditions on that income.4 Individuals can work or not work, make whatever life choices they want, make however much other money they can, and still they will receive a basic income that is the same as what everyone else receives (possibly dependent on age, but no other factors). This makes UBI different from welfare systems that are conditional, variable, or that provide partial support.

I have plenty of criticisms of current implementations and dialogue around AI, but I have utmost mathematical appreciation and respect for the technology itself. Researchers are creating and implementing such deeply interesting ideas at dizzying speeds and it’s incredible to follow.5 I also like Universal Basic Income, despite agreeing with some of the criticism. I’m very optimistic about what humanity could achieve if fewer of us had to spend so much of our finite lives worrying about our basic needs.

It’s increasingly popular to pair ideas about AI and UBI, particularly among the tech elite,6 and at first the pairing made sense to me. AI is already replacing the jobs of translators and customer service work, and with self-driving cars just around the corner the entire transportation industry will be upended, with other industries not far behind. UBI might go from being an interesting research topic to a societal necessity once AI takes our jobs. When no one can find work, we are going to need some way for the economy to weather the AI-pocalypse, and UBI is an increasingly commonly proposed solution.7

The more I thought about it, at least for the first year I was thinking about it, the more AI+UBI seemed to have the ring of fairness. When your job is replaced by a robot who can do it for less, who gets the difference? Won’t all that wealth just concentrate into the giant corporations who own the robots and have patents on the AI? It seems fair that these corporations, by replacing your job with a robot that can do it for less, will now have the money to pay more taxes, which through this roundabout way goes back to you through UBI. In a way, the robot replacing you is working on your behalf, freeing you up for other pursuits.

Now, as much as I appreciate the potential of AI to replace a significant percentage of current jobs, that’s quite a different thing from believing AI will replacing all human work.8 I’ve seen projections from 9% to 47%.9 Even recent projections for 20% AI-related unemployment would be Great Depression worthy,10 but it’s not necessarily a disaster, especially if we see it coming and take precautions. There’s a chance that new jobs will be created faster, or at least at the same rate, as we automate the old ones.11

But regardless of whether the singularity is around the corner, the nature of work will change. As more and more existing jobs become obsolete, UBI could allow people to work on whatever they want, even if they’re not employable at market prices. The average person could still afford to live, maybe buy a smartphone, use Facebook, perhaps even study to become a programmer, and generally keep the economy from collapsing from shock and the tech industry facing a universal backlash.

AI-related job loss is seen as a problem, but in the context of UBI it might actually be a solution. How could we afford to fund UBI without the efficiencies and cost savings of AI and robot labor? And what if people choose not to work because their basic income is enough? AI and automation can take care of all the work that needs to be done, with a surplus left over. It all fits together, it all makes so much sense.

Freeing-Up Human Potential

Personally, I find the idea of UBI very attractive. I’d love to have an income stream that doesn’t depend on other people’s wildly unpredictable valuations of my own hard work on a continuing day-to-day basis! I have no fear of my skills being replaced by AI, but my skills are weird and specific, which makes them alternately highly valuable and completely unwanted. All the research seems to agree that money and happiness are highly correlated at least up to the point of covering basic needs, with the only debate being just how much they are correlated beyond that and by what measures.12 I have more than enough to cover my needs at present, but it sure would be great to be guaranteed an income even if my skills go out of fashion. It’s difficult for me to imagine anyone not wanting that.

UBI would also allow people to develop whatever weird specific expertise may or may not end up being marketable. Some people might end up with just an unusual hobby, and others may end up with a vital job in an industry that didn’t exist when they started studying.

Becoming an expert in a potentially important future field is a risk. If we want to incentivize taking that risk, we can’t force individuals to bear the entire burden of the risk. As the nature of work changes, it makes sense to provide people the security that allows them to develop skills that may or may not become relevant to society. And even if AI truly does replace everything and only the highest-level AI programmers can do work with real market value, isn’t it worth incentivizing everyone to learn programming so that potential geniuses have a chance to develop?

UBI would also allow people the time and space to develop skills that are of cultural value but not necessarily rewarded monetarily at present. Art, music, history, even teaching, tend to not lead to very lucrative careers but benefit all of society. With the time and space given to humanity by AI and UBI, perhaps we’ll soon be entering a great cultural renaissance. Perhaps humanity will be wealthy enough to compensate the work that goes into developing these passions, more than we do today.

I like to imagine that in the right culture and context anyone can learn how to create meaningful work for themselves, or join organizations or groups that will aid that process, even if they don’t strictly need to work for income. In this sense I think UBI is really promising, and research will tell us more about how to create a healthy implementation.

All these things make UBI seem like a good idea regardless of whether the economic AI-pocalypse is actually coming for our jobs. Maybe all we need to survive the next wave of technological unemployment is a safety net for some percentage of people as the economy adapts, but we still decide to guarantee everyone a basic income as a universal right. Maybe we’ll completely overhaul how we do work, education, and infrastructure, in a way that allows people to develop their own potential to benefit all of humanity.

Criticisms, Despair, and Meaningful Work

I’ve thought a lot about the common criticisms of UBI, though they are not ultimately what changed my mind about UBI+AI’s supposed synergy. The simplest criticism is that it would be too expensive, though this criticism doesn’t apply if we’re assuming we’re implementing UBI because of AI’s incredible human-replacing capabilities.13 Another common criticism is that UBI would destroy the economy because people would decide not to work, though there’s no evidence for this and some against.14 Finally, there is the perennial criticism that if you give people money they will just spend it on drugs or something, which has been generally debunked in study after study,15 though who knows if the AI+UBI scenario would be different for some reason. In this piece I’ll focus only on criticisms that are directly related to the AI+UBI scenario.

Given freedom from work, would you then choose to pursue happiness, or spiral into a despair brought on by feeling useless to society because your work isn’t needed? Would you spend time bettering yourself and developing the skills that AI cannot replace, maybe pursuing a degree, or an art career, or teaching, or volunteering for your local animal shelter? Or would humanity stagnate until there’s not enough people to keep the AI systems going to support humanity?

Part of me reacts against the concern that AI will lead to the average person feeling worthless. Tech leaders and aspiring startup founders are not exactly known for their humility,16 and in certain company I wonder how much of the concern over the worthlessness of future humans is a projection of an elitist belief that the average person is worthless. One must always be suspicious when a leader seems to think all of humanity is headed for oblivion aside from themselves and their chosen elite.17 Still, I admit there is cause for concern that AI-related job displacement might lead many people to feel worthless even though they aren’t, or falling into economic despair due to lack of meaningful work, with or without UBI. US culture especially encourages people to tie worth to wealth.

There’s an apparent link between economic despair and deaths of despair, a term that encapsulates deaths due to suicide, drugs and alcohol overdoses, and certain kinds of violence.18 While technology and medicine is better than ever, life expectancy is falling in the US due to an increase in these kinds of preventable deaths.19 Intentional suicide is the #10 cause of death across all populations.20 The opioid crisis is truly massive, with tens of thousands of deaths due to overdose each year in recent years, and millions of people now misusing opioid prescriptions.21 There is also a pattern where those in despair sometimes choose to turn their violence towards others instead of themselves, particularly their own family, sometimes coworkers, occasionally strangers. While the homicide rate has generally fallen through the past hundred years, including the past few years, certain kinds of homicide buck the trend.22 Many are preventable.

Welfare is commonly criticized for being expensive, paternalistic, and for incentivizing avoiding work. But there’s a deeper criticism that beyond keeping people trapped by disincentivizing work, it is also a trap in that it functions as a payoff to keep desperate people from doing desperate things, and instead it keeps people quietly struggling in a system they don’t fit into rather than fixing the system or the economy. It can be seen as a way to sweep economic inequality and cycles of poverty under the rug. Those with power are willing to pay for an expensive system if it means the have-nots won’t cause trouble.23

There’s a big difference between welfare and UBI in that UBI is universal and does not change when reaching some income threshold, so there’s no incentive to avoid work if you want it. The deeper criticism is still troubling, however. UBI in isolation would patch up the problem of technological unemployment while increasing the gulf of inequality. If AI really ends up being all the things the headlines say it is, then the oft-proposed $1000 a month basic income is a very small price to pay to keep people from revolting against the status quo, at least if you’re one of the tech CEOs or investors who will be raking in all this new wealth.

Two more criticisms of UBI may interact strangely with the AI scenario. The first is that UBI is a big enough economic change that we can’t assume it’s like giving someone money in our current economic climate, for example prices of basic goods may rise in proportion to UBI. In the AI scenario the concentration of power would make it very easy for corporations to take advantage of people’s extra cash by raising prices in absence of a competitive market, or to manipulating the market in whatever way a company’s AI predicts will create the most profit. The second criticism is that UBI isn’t truly universal if implemented within a country. Technology, on the other hand, works in a very international space. In the scenario that silicon valley companies create AI good enough to provide for US citizens, I can think of several ways state dependence, international dynamics, and nationalist protectiveness could lead to trouble, though such speculation is largely irrelevant to the rest of this piece.24

So that’s roughly what I was thinking about AI and UBI in 2016-2017. I always knew there were pros and cons, tons of research that needs to be done, potential problems to sort out, and concerns around economic inequality and wealth concentration, but AI’s synergy with UBI made it seem like an inevitable pairing. If we could make sure that the wealth generated by AI technology really is redistributed via UBI rather than hoarded by the already wealthy, it could be an incredible game changer for human potential.

Through 2018-2019 I’ve learned more about other potential options, and more about the realities behind AI. I now think that while the above is all true, there’s more to the story, and AI+UBI may not be such a good pairing after all.

Part 2: Against the Obsolescence of Human Intelligence

Dangerous Dogma

It used to seem trendy or countercultural to pronounce humanity doomed to irrelevance as robots and AI do everything better, faster, and cheaper. It was like privileged knowledge, known to only the initiated. Something fun to wax rhetorical about while out with colleagues or killing time on the internet. No one who claimed to believe these things would consider staging an actual revolution or putting their lives on the line for the cause; it’s just trendy tech talk with no repercussions.

Today the idea of the impending obsolescence of humanity has gone past trendy visionary scifi to harmful pervasive dogma, and it already takes active work not to perpetuate it, especially if you work in the tech industry. Of course AI will do everything better, faster, cheaper! The only question that remains is how to construct dignity and meaning for the billions of unnecessary mortals who aren’t elite hackers or wealthy shareholders!

It’s easy to make fun of such conversations and I’ve done my share of eyerolling, but isn’t there some truth to it? How many of our jobs are really safe from AI automation? What will humanity do?

This section is about how AI programs are written by humans and use human-gathered data, a fact so obvious that it often gets completely dismissed as if it were not true. It is also about the way current culture obscures the sources and value of that data through sheer force of will. Very intelligent people with deep technical understanding of AI have no special immunity to cultural blind spots, and blind spots by nature can’t be seen even when you think you’re looking directly at them.

Collective Intelligence Algorithms

The classic wisdom of crowds example25 is that the average of many people’s guess about something (such as the number of jellybeans in a jar, or the weight of an ox at a county fair) is much closer to the correct answer than most people’s guesses. You could write an app that collects people’s guesses and computes the average, and maybe even get some funding if you compute the average using a neural net rather than the straightforward way.

At a smaller scale, collective decision making is a normal daily occurrence for most people, whether it’s deciding who makes dinner, what movie to watch, or who gets the last cookie. Sometimes people talk it out, but people often find it easier to use algorithms such as taking turns, flipping a coin, or deciding based on the day of the week. Even deciding based on some cultural structure of authority, such as the eldest makes the decision, can be thought of as a very simple algorithm.

Some of these collective decision making algorithms are designed to be fair through symmetry, as when taking turns. Others are more sophisticated, such as “You split I pick”, where one person splits something into two parts (such as a piece of cake) and the other person gets first choice of which part to take. “You split I pick” is brilliant because not only does it incentivize a fair outcome, but it takes advantage of the intelligence of both parties and their abilities to judge portions. It is also both collaborative and competitive: it works when both parties behave “selfishly” in a shallow way, but they both want a fair outcome. It would be in bad taste for the splitter to cut a cake into two oddly shaped parts of misleading geometry that only the splitter understands, for example.

For slightly larger groups, there’s a host of algorithms people use with the expectation of making better decisions. Voting is common, and so are ad-hoc variations that people come up with to suit the situation: we vote but adults get two votes and kids get one, we pick a restaurant at random but anyone can veto, we host the reunion near the average of where we all live but throw out the outlier who lives across the globe. We solicit recommendations from people we know, we write lists of pros and cons or of needs and wants, and we assign points based on invented criteria.

And note that when we frame it as collective intelligence, it’s clear that the algorithm doesn’t decide for us, it just provides a possible answer that then we decide if we can live with. If an ad-hoc algorithms gives an answer that doesn’t work for our small group (say, putting the location for the family reunion in the middle of the ocean), there’s a good chance that we “fix” the algorithm until it gives us an answer we like. We might realize that one particular thing should count for more votes than we had originally given it, or that some things aren’t really that important. In AI terms, you might compare this to changing the weights and biases of a network through backpropagation to lower the cost, but in both cases the changes are made to serve a human judgement of what an acceptable result looks like.26

Voting systems are interesting by themselves, and I’m tempted to make a comparison between AI and democracy. Education is a founding principle of democracy, because a democracy is only as good as its voters, just as any algorithm is only as good as its data. Many groups advertise their democratic voting process as if that alone made it good, but the benefits of collective intelligence cannot be reaped unless the democracy accommodates and respects a diverse voter base capable of educating themselves on diverse materials.

If people have the education and ability to come to their own beliefs, the combination of many partly-wrong individuals will shake out to reflect a mostly-right decision. Misinformation and noise in various directions cancels out rather than becoming amplified. When there are systematic biases, or when too many people follow the same news sources, or become too grouped together and aligned in their beliefs, the entire curve shifts in that direction and collective decision making reflects that bias.

AI systems may have more sophisticated ways to combine people’s input than simple majority voting mechanisms or averaging, but they are still combinations of people’s input. There is nothing in an AI that knows how to be smarter than people’s collective wisdom, it just knows how to be smarter than our previous algorithmic approximations of collective wisdom. As a corollary, there’s nothing special about AI that would make it do anything more than approximate our collective foolishness when we are being collectively foolish.

AI is Collage

To quote M Eifler’s “We Are Collage: Dada, Instagram, and the Future of AI“:

That cancer-screening AI might get it right more often than any individual doctor, but that’s not because it’s “smarter” but because it uses the knowledge of thousands of doctors all collaged together. - M Eifler

I find the collage metaphor tremendously helpful. Collages require source material, and if you’re intimately familiar with that source material you’ll recognize it in the collage. M Eifler also made the striking insight that the intelligibility of machine learning is less about understanding the algorithm, neural architecture diagrams, or being a mathematical genius—it’s about familiarity with the dataset. You can have written the algorithm yourself and still find the results mysterious if you’re using unfamiliar data, and likewise, you can not understand the algorithm at all but still find the results unsurprising if you’re intimately familiar with the data.

Data isn’t like a battery you can switch out to make an algorithm run; it is an essential, central component. Data cannot be an afterthought, data cannot be ignored. It doesn’t matter if you can write a GAN27 from scratch in Haskell28 or compute a gradient descent iteration by hand with pencil and paper.29 A neural net run on Mozart has Mozart at its core, and to understand the results you need to know Mozart. If you’re using ImageNet30, you’d best be prepared for a lot of dogs.31 The AI isn’t just “looking at” tens of thousands of dog photos, the AI is dog photos. The data is the fabric, and the code is just the stitching.32

I understand that new kinds of glue might seem very exciting when first invented. I don’t mean to say glue technology is not an important science, I think glue is wonderful and amazing and useful and powerful, and I certainly appreciate the intelligence of those who understand the molecular composition of glue that makes it work. But glue exists in service of the things you glue together. Glue does not make paper obsolete.

When I listen to music “compositions” generated by AI, I can hear the collaged and combined bits from their data sources. The average listener might not hear beyond “yes, this definitely sounds like a music,” and be quite impressed because they are told an AI created it.

In other cases, the listening experience is like reading a Markov chain of text. I am not surprised the AI could copy words and mash them into locally plausible sets, but it makes no overall sense. Meanwhile to those less fluent in music, I imagine it’s like looking at a Markov chain in another language. If you don’t speak French and are told here’s some impressive creative French written by an AI, it probably looks convincing enough.

In the best case, the result doesn’t seem particularly more sophisticated than Mozart’s aleatoric compositions from 1792 where you could “compose” your own piece by rolling dice to select and combine different possible measures of music according to specific rules.33 Mozart both wrote the measures and the rules, so of course the modern performer attributes the resulting composition to Mozart, not to themselves. But I can just imagine the headline: Music Composed by Dice Proves Mozart Obsolete

The point, though, is that for music and other art-based AI it is hard to ignore the fact that attentive, valuable, human work went into creating the corpus the AI draws from. Without the existing fruit of human creativity, we couldn’t write programs to copy it. Unfortunately, like pre-teens exclaiming “I could do that!” when being introduced to the work of Jackson Pollock or John Cage, the industry applauds shallow copies with no recognition of the physical or conceptual labor that went into their source.

I don’t want to give the impression that shallow AI copies don’t involve any labor of their own. In fact, they often involve more labor than what they purport to replace. How many hours does it take a programmer to create an inferior shadow of what Mozart (or one of the many thousands of living musicians skilled at improvisation) could improvise in real time? Not to mention that the software will have dependencies on libraries, languages, and software that add up to many lifetimes of labor put in by tens (or often hundreds) of thousands of individuals.34

I’ve never had much tolerance for propaganda about how mysterious machine learning or neural nets are, as if computers are doing things mere humans cannot possibly understand, and I’ve got more than a few bones to pick with how AI is covered by the press. Of course those invested in AI are going to try to sell the most impressive-sounding story they can come up with, but then this propaganda gets repeated by news outlets, “influencers”, and everyone else. Neural nets are no more mysterious than any other mathematical entity that seems impossible at first glance, such as Fibonacci spirals in plants, the fourth dimension, or the emergent patterns of cellular automata,35 but people’s mathematical hang-ups serve to distract from the thing they actually don’t understand about AI, which is about people and culture.

Cultural Evolution Has No Endpoint

Critics have been announcing the end of human innovation for as long as we’ve had the concept. In the late 1800s art was dead and “Modern Art” was a malignant symptom of artists who knew all the masterpieces had already been painted and all that remained was to paint badly. Art ended again in the 1960s with Danto’s essay “The End of Art”, motivated by Warhol. In the early 1900s Schoenberg put the final nail in the coffin of music, and 50 years later John Cage put the final nail in again. Gödel’s incompleteness theorem was pronounced the end of mathematics, and even the human mind was figured out, thanks to behaviorism and Pavlov’s dogs.

Of course, now we know that in the late 1800s art was just getting started with new innovations into surrealism and abstraction. We know that music critics obsessed with the avant-garde in the early to mid-1900s were completely overlooking the development of blues and jazz that led to rock, and then missed the ball again in the 1970s with the development of hip hop. There will always be critics who look at whatever exists and pronounce it the end, and without fail these critics are making judgements rather than prophesies.

We now know that Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem didn’t destroy mathematics but opened it up, and like art, mathematics found new power in abstraction.36 We know that contrary to behaviorism, human minds don’t simply receive sensory data as input and spit out a behavior, but that the mind plays an active role in what we sense and how we interpret it.37 Physics finally came to terms with itself, after a bumpy path from Newton to Einstein to Noether to Planck and beyond.38

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions Thomas Kuhn argues that the work of science is never finished. We can continue to improve our understanding and update our worldview, but there is no end point where our understanding of the universe is complete. The same has been said for other fields of study and aspects of human life, including art, culture, and social justice, where those expecting a final dataset of all the right answers are sure to be disappointed. There’s no reason to think we’ve suddenly reached peak humanity, or that we ever will. There is no end of history.

We’ll always have new data for AI to work with, which is good because there’s no evidence that AI will ever be able to do anything more than efficiently collage together the intelligence of people. Collective human intelligence is tremendously powerful, and as we create better and better technology I think we’ll be continually surprised by how intelligent our species can be when we come up with good systems for working together.

The idea that AI might “get enough data” is extremely pessimistic because it means humanity has become stagnant. It means we are serving the needs of technology rather than vice versa. It’s like that sad moment of finally clicking on that show Netflix has been recommending for a year despite that you’re genuinely uninterested, except it’s that moment forever.

I’ve had my views on AI called pessimistic because I don’t think it will ever be smarter than people. I don’t expect to find technological utopia in a product, a company, or a benevolent AI overlord who supplies all my basic needs. Rather than looking outside ourselves, I believe in looking within. I’m quite optimistic that people will become smarter than people, and I expect the automated collages of our intelligence to appear smarter along with us.

Maybe AI is part of whatever tool boosts the cognitive capabilities of humanity in the same way language, literacy, mathematics, and the scientific method expanded our abilities, not just through technological artifacts that exist outside of us, but inside the very way we think, see, and feel.

Given what we know of history, I believe we are a very long way from finding the limits of the capabilities of the human mind.

Part 3: The Impending Obsolescence of Artificial Intelligence

AI Purity Culture

The industry will admit that for now we need to use human-created input, but there’s a kind of cult thinking that this is a temporary situation and that the technology is only incremental improvements away from “pure” AI creations.

The “purity” bit bothers me a fair amount. It’s not just an assumption that AI technology without reliance on human-created data would be superior. Ideas of purity contain an implicit assumption that pure AI should be superior. That it would be better to not have to use human-created data, and that human-created data is something we should aspire to grow beyond.

Despite my forays into the industry, I’m a pure mathematician at heart. Nothing is more beautiful than the most abstract bit of mathematics, or the most efficient algorithm, removed from concerns of reality or practicality. But AI purity culture obsesses over another kind of purity entirely. It’s as if admitting that humans create data is reminding the industry of an unpleasant fact, something best left behind closed doors, something we don’t mention in polite company. Only those without vision would think it necessary to point out the human sources of the data, surely! It’s like mentioning child labor at a fashion show, or reminding a hungry foodie how their sausage was made.

I’m reminded of something from our VR research days. A company I won’t name was frequently making the VR news with big claims about something their proprietary software could do algorithmically. Mathematically this seemed suspect to me. We met with a room full of young men pitching their technology with all the jargon in the book, but unable to answer basic questions that only someone in their field would know to ask. Months later at an event we ran into someone who worked there. Her job was to do by hand the thing they claimed their algorithm could do. The entire rest of the industry pretended she didn’t exist, and the company truly believed that any day now, maybe if they just hire one more rockstar developer, they’d finish up this algorithm they were pretending to have, so she wasn’t worth much anyway.

Here’s the cultural result of techie propaganda taking over the headlines. The actual people making technology work are devalued and erased, because culture is deciding their work is not worth very much, because we must not allow our lofty visions to be sullied by the realities of human labor. Meanwhile, untold amounts of venture capital get spent on rooms full of developers who make systems that exist to hide human labor under a veneer of technological progress. In the case of the woman at the trending tech startup, at least her work was legally recognized as work and so she’s protected by labor law whether or not her employers think she’s worth anything, but sometimes it is gig workers making $.01 per job,39 or an unsuspecting person on social media or simply walking with their phone in their pocket. As AI becomes more ubiquitous, the people doing the data labor and making it work are all of us, all the time.

This problem is highlighted in the book Who Owns the Future? by Jaron Lanier, which has been very influential to this piece.40 Lanier calls platforms like Facebook and Google, which go so far as to spend billions creating “free” services to offer in exchange for collecting mountains of data, siren servers. Like siren song, the attraction of free social networking, messaging, email, and other tools leads people to leap unthinkingly into exploitative user agreements and privacy violations.

The companies that go out of their way to collect this data about you are not doing it because it is worthless. There’s a reason companies and governments can’t just make up data, run algorithms on their made-up data, and get useful results. Valuable data results from, and is deeply interwoven with, the work of living a human life.

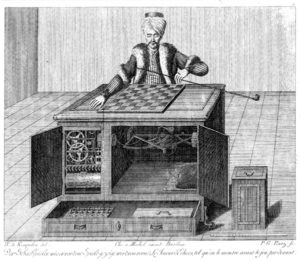

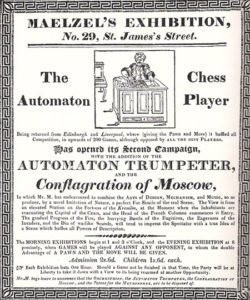

The Mechanical Turk

Wolfgang von Kempelen unveiled the Mechanical Turk in 1770 to out-do his perceived competition and impress the Empress of Austria, perhaps not too dissimilarly from how AI folks compete to impress today. Interestingly, this was explicitly a competition between illusionists, and Kempelen introduced the Turk as an illusion. If anything, this increased the allure of the idea that maybe the trick was that it was not an illusion, and the secret was not revealed until the 1850s.

For 80 years the Mechanical Turk, or Automaton Chess Player, made the rounds in exhibition after exhibition. But while some may have been fooled, many suspected that there must be a hidden player in the box beneath the automaton, and it isn’t clear to me that the audiences of these exhibitions were any more fooled than any audience at any magic show. We might say “the magician saws a lady in half”, and we might say we were convinced, but that’s just the way we talk about the medium. The illusion is the point, and in normal dialogue we participate in the fiction that the illusion is real.

The Turk could do more than play chess: it could gesture and use a board covered in letters to answer questions and communicate. Chess was its way of proving its intelligence and making a show against opponents such as Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin, and the quantifiability of games won makes chess games good for headlines. Still, it was also a chatbot, and I think this aspect tends to get left out of history and modern recounting exactly because it ruined the illusion of the Turk being an automaton. People want to be fooled by magicians, and chessbot is more believable.

Similarly, modern AI illusions are not trivial illusions at all; they involve ingenious work by their creators. Like Kempelen, most AI researchers will be the first to say there’s nothing mystical about what they’re doing, but the headlines and advertisements for the Turk were as sensationalist as anything you’d see today. The audience wants to be fooled. Humanity also has a tendency toward fetishizing the artificial. We love a good excuse to suspend our disbelief in a way that objectifies or dehumanizes others.

Sometimes we willfully ignore the person hidden in the box, sometimes we don’t see the box because we’re the ones in the box.

Modern Mechanical Turks and Ghost Work

Like its namesake, Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk)41 is a complex system that converts human labor into apparent automation. MTurk is a data marketplace where you can post data tasks that will be sent to gig workers around the world who will, for example, label photos for as low as a penny apiece. Or, as a worker, you can sign on to do data tasks for pennies apiece.

This work can be used to train AI, though that is often a secondary use for the data. Many data jobs need to be done for their own sake, whether it’s a comment that needs to be moderated, a video that needs reviewing, or a product listing that must be sorted. Only afterward is that data then used to train an AI with the hope that next time the task can be done automatically, yet instead of valuing the need for this labor the industry performs the mental gymnastics of pre-retroactively depreciating the value of the task based on imagining it could have been done by an AI in the first place after we have the data.

As with the original Mechanical Turk, human labor is hidden. We might know there’s thousands of people involved, but AI culture tricks us into believing none of them really count, that the workers are interchangeable, and that the work is ultimately replaceable.

The cult thinking is that datasets such as ImageNet, a dataset of over a million labeled images frequently used for AI training, can train AI that will replace more work than the dataset took to make. This seems unlikely for ImageNet, which was labeled by 49,000 workers over 2.5 years,42 and that doesn’t count the work of creating the photos. People like to imagine that if this bit of data doesn’t replace more work than it took to make, maybe the next one will.

ImageNet is frequently used in academic work, student work, and in contests where the goal is to write an improved AI. By having one standard dataset, the models can be fairly judged against each other. It makes sense to obsess about models and ignore data when you’re working on learning, researching, or improving models! But real-world AI applications improve by gathering more data where the model is failing, rather than changing the model to try to accommodate a hole in the data. The effectiveness of gathering good data where and when it’s needed is exactly why academic work cuts out that variable and uses standard, static datasets. Students and hobbyists are so used to writing models to fit static datasets that perhaps sometimes they forget that these exercises don’t reflect industry reality.

Every bit of data comes from somewhere, but if people imagine this hidden labor being done at all they usually imagine it is done by unskilled workers in developing countries who are in desperate need of the money and thrilled to have this outsourced work. The book Ghost Work by Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri examines the realities of data labor and the people working for platforms like MTurk and Microsoft’s Universal Human Relevance Service (UHRS).43 The realities of data labor and those doing it may be different than you imagine.

According to their research, on MTurk almost 70% of workers have a bachelor’s degree or higher, globally. On UHRS, which has higher entry standards, it’s 85%.44 Comparatively, 33% of US adults have a bachelor’s degree.45 A 2016 Pew Research Center study that focused on US workers on MTurk found that 51% of US workers on MTurk have a bachelor’s degree.46 The same Pew Research Center study also found that the majority of US workers on MTurk were making under $5 an hour. Federal minimum wage in the US is $7.25. This is one of many strategies to innovate revenue through disrupting labor law, as this kind of on-demand gig work is currently uncategorized and there is no precedent to protect it.

This allows outsourcing to skilled, educated workers within the US at non-US prices. According to MTurk Tracker,47 the majority of workers on MTurk are in the US. Part of this is because jobs on the platform often specifically require workers to be in the US, whether it’s because academics want to collect US data or because a US marketing team wants to survey their target customers. Some work requires fluent knowledge of American slang, such as content moderation and translation. For non-native speakers it’s a risk to take work might get rejected, losing them pay and earning them a negative mark on their record with no opportunity to dispute the rejection or loss of pay.

Pure AI is Obsolete

You can make many kinds of AI 95-99% accurate without too much fuss, but that last 1% seems to be a moving target. When millions of people use a service multiple times a day a 1% catastrophic failure rate is enough to sink a company. The most reliable, fastest, and least expensive solution is to simply include human judgement as part of the architecture.

The authors of Ghost Work call this the paradox of automation’s last mile. In the traditional last mile problem, for transportation logistics and laying cable to homes, people’s commonalities in location mean that shipping and infrastructure can easily and efficiently get 99% of the way there, but it’s the literal or metaphorical last mile that creates the bottleneck as routes must diverge based on individual houses. While you can compute increasingly efficient shipping routes and cable layouts up to a point, there is no layout that avoids the last mile problem.

Automation’s last mile is the analog that applies to AI services. Our commonalities can get an AI 99% of the way there, but our individuality remains, and so serving individuals requires constant labor along that last mile. Language today may be 99% the same as it was yesterday, and even you might be 99% the same as you were yesterday, and that’s all AI knows how to account for. Incremental improvements in AI can’t get us that last percent—the problem is of a fundamentally different kind.

The big tech companies relying on AI as part of their infrastructure have already arranged their logistics to handle automation’s last mile through on-demand data labor. MTurk launched in 2005 to solve its last mile data labor needs, in the past decade it has increasingly become industry standard to automatically and algorithmically hire on-demand labor as it is needed for specific tasks.

Websites like Facebook, Google, Twitter, eBay, and YouTube are not purely technological marvels of computer engineering that exist as digital objects on their own; they cannot be boxed and sold independently from their work force as if they were products rather than companies. Pre-packaged independently-running software is an old paradigm. Pure AI is obsolete and has been replaced by automated collages of human intelligence.

Multi-Layered Human-Computer Architecture

Today’s developers don’t write computer programs, they write computer+people programs. “Algorithmic” services frequently operate through automatic API calls to human beings through platforms like MTurk and CrowdFlower when the algorithm needs help. These workers then validate data, handle flagged content, or shore up whatever parts of the algorithm tend to fail, sometimes in real time as a transaction is being made.

The engineer who writes the algorithm acts as a kind of manager, but with the algorithm as a buffer. By pretending it’s the software managing the hiring, the engineer keeps a safe distance from any feeling of responsibility toward workers. They also avoid other costs and responsibilities of managing workers, not by shifting it to the AI but by shifting it to the workers themselves. Workers are expected to sort through jobs and match themselves to suitable tasks on their own unpaid time, and workers bear all the risk if their work is deemed unsatisfactory or is not delivered on time. The engineer also doesn’t have to worry about providing office space, hardware, or a safe working environment. There is no break room, no watercooler, no benefits or insurance, no HR. AI can cut a lot of costs just by dividing work into chunks small enough that existing regulations don’t recognize them as work, but it remains work nonetheless.

Once the human is hired for a task, sometimes their work requires looping back around to another algorithm, as when searching for an unknown term in a piece of flagged content. Their search leads them to another piece of content written by a human, such as an explanation in a slang dictionary. After they submit their work, more alternating layers of humans and computers exist up the chain as well.

Content moderation is a complex task. A pure computer program alone cannot reliably identify whether a post is hate speech or not. Language is subtle and fluid; as posts get flagged people change the way they talk both naturally and purposefully to get around the automated system. People are continually inventing new symbols, metaphors, images, and code words that can only be flagged by an AI if that AI gets new data from human beings who can provide labeled examples of how things have changed. And because this has to be done in real time in order for social media giants to stay family friendly, the very architecture includes asking human beings what to do. An engineer is paid a lot to create a system that allows an unpaid user to flag content, automatically sending it to someone else who makes below minimum wage to make a judgement call.

Hate speech isn’t unique in its constant evolution. All language evolves, and any AI that hopes to keep up is going to rely on new examples added to its training data. When the task is less urgent, it’s possible to avoid the direct API calls to paid workers and instead get your human-created data by eavesdropping on online conversations and comments, or through correlations with human-written captions and human-flagged content. Many methods of data collection are layered together, including AI hiring humans who gather data from other humans. Modern systems have human input built into the architecture rather than waiting around for slow periodic updates to a “pure” algorithm.

Another example is facial recognition, which is sometimes used for real-time identity verification. Current facial recognition algorithms are known for having gaps in their functionality due to gaps in the training data (for example, models that fail when presented faces with dark skin tone because they were trained on pale faces), but facial recognition isn’t something with an end point where once we collect all the minorities we’ll have the perfect system. There will always be new trends in makeup, facial hair, glasses, tattoos, fashion, and body modification. Faces will continue to reflect a diversity of genetics, abnormalities, injuries, and medical conditions. And there will always be new ways that people (or other AIs) try to exploit the system through the edge cases.

In Ghost Work, the authors cite an example where an Uber driver sends in their photo for identity verification. The system pretends to think for a bit, and by the time he is to pick up his passenger he is verified. Behind the scenes, the AI could not recognize his face because he shaved his beard, and so the images were sent to an on-demand worker who took the job and verified him in real time. As far as the driver and passenger knew, the automatic system worked perfectly, and the person behind the scenes remains a ghost.

Ghost Work refers to work done by people who at least know they are working, and are getting paid for it, even if some aspects of the system are exploitative. Data labor is also done unknowingly and uncompensated by almost everyone with an internet connection, whether through explicit data tasks like re-captchas or by more subtle means such as the metadata on uploaded images. An on-demand worker might be underpaid for a facial recognition task, but the people tagging their friends in photos on Facebook and Twitter aren’t paid at all.

Let us not forget the labor that goes into creating photos of faces in the first place, for example the photos on driver’s licenses, which are often used by various agencies as if they simply existed for free. Every one of the millions of drivers license photos are the result of someone going to the DMV, waiting in line, providing their information, and participating in a photoshoot. Every person who provides their height and weight grew up in a world of cultural messages surrounding height and weight, and through the work of living in that world their data becomes more useful, more correlatable, more than a random number. Random pixels or made-up faces are worth nothing to these systems, but real faces take work and time to grow. Beyond their pure geometry, faces contain a wealth of information from makeup, facial hair, acne, skin tone, hairstyle, and expression. Having this data collected at the DMV only requires volunteering a few hours of a finite, irreplaceable, human life, but creating that data requires living a finite, irreplaceable, human life.

When it appears as if AI is replacing human work, that is an illusion created by entities that are shifting work from legally recognized employment to on-demand gig work and to unacknowledged unpaid labor, putting AI where it is visible and humans where they are invisible. AI is a threat to jobs, not work, and it’s not the AI doing it but the startups and companies using it to enter a fuzzy legal space where there’s no precedent of enforcement under existing labor law.

Labor Rights for Ten Thousand Women in a Box!

You may have pretended to talk to a woman named Alexa, Siri, or Cortana, who lives in a rectangle, tube, or brick. You may even trust that your direct vocal input is not being recorded and saved, but data based on your recorded input certainly is. Every time you repeat something that Alexa didn’t catch the first time, you “help Alexa get smarter.”48

It seems every major tech company is selling the illusion of a woman in a box these days, and as with the classic magician’s illusion we want to believe the magician. In one version of the classic illusion the magician succeeds because there’s actually two women—one playing the head and one the feet—but in the modern version there’s ten thousand women in the box, each contributing a tiny chunk of a person that gets collaged into what the audience perceives as one single AI assistant. As with the magic show, we don’t pay the assistant. We pay the magician.

A famous, world-renowned magician can afford to pay all the women in the box whether we know they’re there or not, but what happens when he tells the women they should be happy to work for free in exchange for fame, exposure, or experience? Maybe this is the only box in town, and even other magicians in other places are following the same business practices. It’s not as if they can quit and get a higher paying job somewhere else, especially without developing more experience and skill, so women will keep on volunteering for box jobs hoping for their big break.

This is not so much a metaphor as it is history, and similar things are happening on internet platforms today. People volunteer their time to make content for platforms like Instagram and YouTube, hoping to eventually catch a break and go viral. If they do hit on something great or develop their skills enough to start making money, both they and the platform benefit. Either way, the platform gets all the benefit of a risk pool of content creators that could potentially bring value to the platform, while shifting the risk to the creators who are investing their lives.

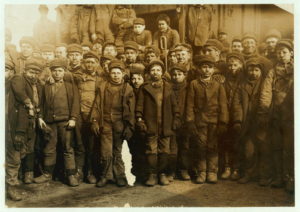

When we think about data labor markets, as with any labor market, we must consider how to keep things from deteriorating to the point that people will do data work in poor working conditions for little to no pay. Current conditions of data labor may not have the same kind of physical hazards that motivated the labor movement in the early 20th century,49 but the psychological hazards of modern data labor are also dangerous, and sometimes deadly. Even those who do become successful on online platforms are often left with lasting health effects attributable to poor working conditions.50

Looking back at the early 20th century it’s easy to see why it’s wrong to lock workers into factories so they can’t leave during the day, or send children to work in dangerous and toxic environments where loss of limb was not uncommon and lasting health effects a certainty, but at one point it was considered normal and tolerated as a fair, “voluntary” exchange for what the companies provide. I wonder how we’ll look back at today’s dehumanizing and abusive online environment, the hypervigilance required to succeed on highly competitive platforms, and the apps designed to be addictive and free in exchange for clicking “yes” on the permissions and privacy agreement. I wonder what lasting health effects we’ll find in children who grow up doing unpaid data labor for the platforms that profit off their clicks, comments, and content.

Human labor is in more demand than ever, to the point that ordinary people are on-call 24/7 on-demand to fulfill the needs of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Google. People are getting up in the night to look at their buzzing phones, checking their notifications during dinner, and scrolling on their laptops while they talk on the phone. Notifications aren’t on by default because these platforms are trying to do you a favor, they are there because engagement is valuable to them. As pure AI becomes obsolete and demand for real-time data labor increases, we must figure out how to value and compensate this labor.

Part 4: The Value of Data

Data Markets

“Isn’t people’s data worth mere pennies?”

This is the most common question I get about the idea of a data market, or the idea that Facebook or Google should pay people for their data instead of taking it (often without your knowledge) in return for the use of the platform. I asked it too, at first. After all, if you tried to sell your own data right now, you probably wouldn’t get very far. Why would anyone’s data be worth much of anything when the supply is so large?

Who Owns the Future? makes a strong case that data is already hugely valuable and will become more so, enough to allow individuals to sustain a living, so long as they are actually compensated for the use of their data. If individuals were able to participate in a market where they could sell their data instead of expecting it to be taken, perhaps through market forces we’d discover the true value of data and find it to be quite significant.51 Creating a functioning market for data labor may not be an easy task, however. The existing market for data labor certainly doesn’t seem to be valuing it very high, and its fuzzy legal status52 may be preventing it from blossoming into the economic powerhouse of future humanity.

If the data market were more symmetric, meaning the average person might be involved in both selling their own data as well as buying it from others, we might expect a healthy market to arise naturally. As things are, the market is highly asymmetric: a few powerful companies (and governments) find great value in people’s data, and everyone else is a producer and potential seller. In our current culture people have been convinced that their data isn’t worth much, and usually their data is taken without markets having anything to do with it in the first place, or bought at rock bottom prices regardless of what it’s worth to the buyer.

My mathematical opinion is that a good market is not a totally free market, nor a fixed market, but a market that calculates continuous new information. Good regulations, strong unions, and minimum wages are all options we’ve used in the past to lift markets off of rock bottom and get them calculating. Maybe something similar will be of use this time. We don’t need to re-calculate the information that if people’s only option is to work for pennies, they will work for pennies.

Data Monopsony

It is useful to compare to the history, and current state, of labor monopsony. Similar to monopoly, where the market is helpless to correct even a large disparity between how much something costs to produce and how much it is being sold for (leading to unnaturally high prices and exploited buyers), with monopsony the market is helpless in the face of a wide disparity between how valuable something is and what it is being bought for, leading to unnaturally low prices and exploited sellers.

In the case of labor monopsony, workers are unable to find jobs that pay what their labor is worth, regardless of how much profit their employers gain from their employment. Most people do not have a choice as to whether to work. Skills and location usually limit the options of where a person can work, sometimes creating a situation where people must work for whatever amount of money they can get, even if it is not a living wage, regardless of how much money their labor makes for their employer. Those who do have a choice often choose to work because they want to work, and they can afford to take a job at well under what their work is worth to their employer.53

History has shown again and again that monopsony conditions can lead to companies going beyond just paying their valuable workers next to nothing—in some conditions workers will grow increasingly in debt as they work nonstop in unsafe environments where injury and death are commonplace. We’re not just trying to avoid hitting the rock bottom of $0 earned—this is a kind of system that can spiral well into the negative. Labor law in the US keeps standards higher for some categories of workers, but it is still commonplace that extremely wealthy companies profit from the labor even of full-time workers who are paid less than a living wage, which only strengthens the hold employers have over their workers as employee debts increase and they cannot afford to negotiate or look elsewhere.

Data monopsony isn’t quite the same as standard labor monopsony examples, because it also includes the work of people who produce data in addition to whatever other work they are doing rather than with the expectation that it is their sole income. At present, exploitation of this kind of data labor is not easily connected to poor working conditions or increasing debt, because we are almost all doing this kind of labor and there is a general trend of increasing debt as well as a shift of jobs from full time to gig work. People can afford to have their data exploited as long as they also have traditional jobs with all the legal protections gained from the labor movement, but how will that change as traditional jobs are increasingly replaced by temp work and on-demand labor?

Data monopsony isn’t just a result of asymmetric power and lack of urgency, however. Culture has blind spots, and it has the power to overcome all market forces and decide that a kind of work, or kind of person’s work, is simply not valuable regardless of whether it would be in a functioning market situation. Historical examples include women’s work and the piecework of the industrial revolution.54 Eric Posner calls this phenomenon cultural monopsony and makes the case that data labor is the latest subject of this kind of exploitation.55 We are told our data is not worth very much by the same companies who put us through vast manipulations to ensure we keep spending our time producing and sharing such data, and most of us are too used to the status quo “sharing culture” to notice the incongruousness.

At some point we, and I mean all of us, will no longer be able to afford the load on the economy created by exploitative unpaid and underpaid labor. It took until the Great Depression for workers to find the momentum to organize around labor rights in the early 20th century. Perhaps we can learn from history and act sooner this time.

Data Collectives

Something similar to labor unions might be essential, given the history of labor rights. Collective bargaining can protect against the worst exploitations of monopsonies, and can also lead to higher standards of work, so if done right it’s win-win. Data is only useful for machine learning when there is a lot of it, and it works best when collected and organized using the same standards across the set. Any one person’s single piece of data actually is worth very little in isolation, and so people have no bargaining power alone, but collective bargaining for large datasets could lead not only to a more accurate valuation of that dataset and each person’s contribution, but also the creation of larger, higher quality datasets, hopefully avoiding some common pitfalls of AI run on bad data.

“A Blueprint for a Better Digital Society” by Jaron Lanier and Glen Weyl,56 proposes that individuals should belong to collectives called Mediators of Individuals’ Data (MIDs) which negotiate and sell data on their behalf. People can choose one or more of many different kinds of MIDs, perhaps choosing one that pays less but demands more privacy, or that pays more but requires specific skills to gain membership. Some might be run like corporations, some like co-ops. Rather than having to negotiate or accept every individual terms of agreement with every website, your chosen MID would handle the agreement with various apps and services, lowering the cognitive load on society and allowing more effective bargaining for data payments.

I think of MIDs as being similar to unions, although that is controversial amongst my colleagues as the structure might be considered just as similar to a corporation as it is to a union. The key point is that no one has to go it alone, and can work together as part of a company, union, or MID that makes it so they don’t have to do everything themselves or negotiate every single aspect of every transaction. Schemes requiring total cooperation fail just as reliably as schemes requiring total competition, and so there should be many companies, many unions, many MIDs, all cooperating within themselves while competing amongst themselves.

There also will need to be regulatory changes in how we are allowed to control our data and how our privacy is protected. This is essential because participating in systems that collect our data is no longer a choice. Even if you could avoid social media, your data is being collected and sold by institutions like hospitals and banks as well. These institutions may say, and even believe, that they are not sharing your information because they only share basic demographics and anonymized statistics, but promises of anonymization mean very little—once enough data about you has been collected and sold, even innocent-looking statistics can be correlated and traced back to you. There is no longer any technical basis for claiming aggregated data exists outside of the interests of those who made it. The law should reflect this.

The vulnerabilities of aggregated data don’t only affect individuals, there is a public health and security aspect to data privacy. One could argue that as with car insurance and vaccinations it is not just an individual choice. While an individual might decide to take on the risk of giving away data in exchange for free services, and think it’s worth the convenience of skipping through user agreements and using the software that’s easiest, it not only drives down data wages but also makes it easier to de-anonymize others’ data.

Choices surrounding data, privacy, and economic actions are complicated enough that expecting people to represent themselves and make those decisions as they go is setting people up to fail and be taken advantage of, as well as potentially harm others, under the facade of personal liberty. We don’t expect people to be their own lawyers, we deny individuals the liberty to work full time under minimum wage, and car insurance isn’t optional even if you’re personally willing to take the risk.

Jaron Lanier puts forth the idea that perhaps we should consider that membership in some sort of data collective should not be optional, or that it should at least be difficult enough to opt out of that it is no longer easier to just click through user agreements. If MIDs were mandatory, you could choose which MIDs represent you and advocate for your interests, and you might even choose to create a new one if the existing ones don’t cover what the market demands, but you couldn’t choose to be unprotected. If MIDs were opt-out, they should be difficult enough to opt out of that it shows it is a true personal choice and not a matter of convenience.

These are recent, developing ideas that I find fascinating. MIDs may be one factor in creating a data market that is able to successfully reflect the value of data, particularly for data that is currently created unintentionally and collected unknowingly.

Other Market Thoughts

The current framing around selling data, even collectively, might be the wrong way to think about things. It may end up being the case that current market mechanisms are not able to accurately reflect the value of data even with collective action, because we’re still relying on mechanisms that were developed for physical goods and physical labor.

Perhaps we sell improvements to machine learning models, rather than the data that improves it. Maybe we track the sources of all data and collect royalties from the use value of a piece of data every time it is actually used by an AI.57 Digital goods and ownership don’t work the same way as physical goods, and maybe it’s time for an entirely new economic model that is better equipped to handle these differences as digital goods and services make up an increasing share of the economy.

We may also want to work toward a future where the average person will have access to the kind of computing power and knowledge that allows them to participate in the data market as buyers as well as sellers, to further break up the monopsony and create a more symmetric marketplace. If anyone could take advantage of underpriced data, not just large companies, a healthy data market might spontaneously arise and self-regulate. But just as taking advantage of underpriced agricultural labor requires owning agricultural equipment and space beyond what most individuals could ever afford, taking advantage of underpriced data labor requires vast computing resources that currently only a few very large companies have access to. Left to their own devices, computational resource monopolies result in data labor monopsonies.

Tragedy of the Data Commons and Labor Commons

Today’s workers can’t expect a full time job at a single company where they live out their entire career, yet the law still assumes this is the case. We have to figure out where gig work and on-demand labor fit within our existing labor laws, or more likely create new laws that reflect the reality of what labor looks like and is predicted to look like in the future. If the future of work is increasingly fragmented and made of pieced-together gigs, we will need to change the laws to have a healthy workforce that can fulfill the needs of businesses.

Ghost Work compares current on-demand labor practices to a tragedy of the commons scenario, where the common pool of on-demand labor is overworked and left without benefits, health insurance, or a living wage. The authors recommend that new labor laws, universal healthcare, and oversight that ensures the labor pool is able to meet demand in a sustainable way.

This is related to a common complaint among tech founders and recruiters trying to hire programmers. From what I’ve heard, no one can seem to find good hires who have all the skills and experience they want, yet no company wants to invest in training up workers because no one expects anyone to stay at the same job for more than a few years. Every job expects programmers to work day and night on tight deadlines to ship products, leaving them burnt out and with no time or energy to develop their skills, and when they’ve finally had enough they get thrown back into the labor pool where they will have to sprint to prove their worth to the next employer who expects them to make work their life.

The tech industry isn’t alone in making a practice of squeezing everything they can out of employees and then leaving the problem to someone else, creating a true tragedy of the labor commons. But tech is alone in its ability to innovate constant new ways to do it to people who aren’t employees too.

I mentioned the work people invest into platforms like Instagram and YouTube earlier. The scenario in Ghost Work where on-demand workers are overworked also applies. One last aspect is the way in which success on algorithm-run platforms requires conforming to what the algorithm currently wants, investing in what’s trendy or making money in the short term. These algorithms often incentivize working to the absolute limit of what it is possible for a person to do, with unsustainable hours and assuming perfect health and no other life events getting in the way, with a constantly just-out-of-reach hope of success. Innovative or experimental content is disincentivized, as is developing unique unusual skills, as is thinking and expressing independent unusual thoughts. There’s no time and no room for error. All thoughts must be exactly the right amount of pretend-unique such that they capture the clicks and attention of the million people who have the same exact thought while maintaining the fiction that it is independent and unusual.58 Content must be frequent, consistent, and without any variation that might alienate your current audience and cause you to fall out of favor with the algorithms.

The tragedy of the commons is that any hint of growth toward the things humanity values most in the long term, and the things AI will be able to grow the most from, are destroyed before they have a chance to be developed. When systems incentivize full-time always-on participation, and success is a competition between workers or creators for jobs, clicks, and attention, no amount of skill and no height of success is enough to allow you to slow down, try new things, or learn new skills.

Reframing Universal Basic Income

Ghost Work reframes UBI as a retainer base wage for all working adults, which makes on-demand economies sustainable by allowing the workforce to be available and on-call while also giving them the opportunity to update their skills to meet changing demand. Instead of a labor pool that becomes increasingly burnt out and outdated, we’d have a labor pool ready to jump on a job at a moment’s notice with all the skills and creativity they’ve had time to develop between jobs.

In “A Blueprint for a Better Digital Society” ideas about UBI are contrasted with an economic proposal for data as labor through MIDs. When people are paid for the data used by AI, UBI will not be necessary. In a way, UBI could be reframed as a base wage in exchange for the basic data a person creates, with the option of taking on more higher-paying data work in addition.

If AI is really expected to be capable of automating 99% of human work, humanity should be able to negotiate a very good price for the on-demand fulfillment of that last 1%, as well as a good price for the data that makes the first 99% possible in the first place. In a functioning data marketplace, perhaps some people can make quite a lot of money designing good datasets or providing unusual data, but even minimum participation such as your demographic data and public records is valuable because this data is real, true, and uniquely yours.

Ideas about AI and UBI must stop being centered around the value of AI and start being centered around the value of humanity. The bigger AI grows, the more space we have to learn new things and create the innovations that allow AI to grow more. The more valuable AI becomes, the more value there is in the human labor that completes that last 1% that AI can’t do. The more AI can do, the further we set our sights, always setting our goals just 1% out of reach, just barely within the realm of what it is possible for AI-enabled human collaboration. The sky is no limit; humanity will never stop changing and growing, with AI always just one step behind.

Dignity for Data Labor

We must allow individuals genuine, not-set-up-to-fail choices surrounding the data they create—whether intentionally or unintentionally—and allow them full participation in the data economy such that the value of their work can be recognized and compensated.

Some data requires active, thoughtful design. We must acknowledge and honor the work that goes into creating good purposeful data, and allow it to thrive in a sustainable economy.

Some data grows naturally in the space of a well-tended life and needs only be collected to be valuable. We must acknowledge and honor the work of tending your garden, the work of living.

Conclusion

I Changed My Mind

I no longer believe Universal Basic Income is a solution to the economic AI-pocalypse.

I am not worried that the lost jobs of the AI-pocalypse will lead to a mass of people with no way to meaningfully contribute to society, however I am worried about the AI-pocalypse leading to people’s real, meaningful, contributions going unacknowledged and uncompensated.

I worry that people’s genuine enthusiasm and belief in the potential for AI to “outgrow” the need for human data labor will blind them to the realities of human labor conditions now and in the future.

I worry that the cultural forces that already tie money to worth, and income to success, will send poisonous messages to people about how they are not enough, that nothing they do is valuable enough to justify their place on this earth, and that if anything they are in debt to the addictive apps that at least distract them from a perceived pointless empty worthless existence.

I still like the idea of UBI for other reasons, though I worry if it were implemented in the current cultural and technological climate it would do more harm than good. I worry it would be used to exploit data labor from people who are told they have nothing better to do than spend all day on addictive apps. I am worried about such apps being framed as free services, given as charity along with the UBI that gives people time to use them, while in reality those addictive apps are exploiting data labor to make huge profits, of which only a small portion gets paid back through the taxes that fund the UBI system.

I believe the apparent synergy of AI and UBI comes not from them being a radical brilliant solution, but from them being the easy way out, the status quo, the default choice that leads further down our current path of increasing inequality. I believe UBI is not a departure from our current implementation of capitalism, but a validation of it. I believe that the popularity of UBI among tech leaders is likely a reflection of this, and that while many proponents of UBI have good intentions and some are even willing to make sacrifices for it, ultimately UBI would be used to strengthen the business models that made many of these people wealthy, including in some cases business models that only worked through circumventing labor law and exploiting regulation loopholes created by new technology.

I do not want this to read as a denouncement of any particular person promoting the idea of UBI, as I myself was right there with them a few years ago. It is genuinely very difficult to see past an apparently synergistic pairing as compelling as AI and UBI, and very easy to perpetuate harmful cultural things even when you’re trying your best to break the status quo. I write this piece with complete sympathy for everyone struggling to figure out what to do to make the world not terrible, especially as all I have myself are thoughts and suggestions rather than answers.

I am convinced that there is a way forward that is both more humane and more intellectually honest than the standard AI+UBI vision. There isn’t a standard term for it yet, but somewhere at the intersection of Data as Labor, Data Dignity, Humane Digital Economies, something to do with Data Unions or Mediators of Individual Data, I don’t quite know yet, but we are converging on a vision of the future where people aren’t exploited and brushed aside in service of machines but are placed at the center of our social and economic future.

Humans will never be obsolete, and you will never be worthless.

End

Acknowledgements

Jaron Lanier’s work has been extremely influential to this post, both through his published work and in-person conversations. M Eifler’s Data Dignity work has also been essential, which you can find here on this site. This piece has also been influenced by conversations with Glen Weyl, who gave helpful feedback on earlier drafts, as well as Mary L. Gray, whose research and writing has greatly expanded my perspective.

There are many others who have influenced my thinking on these topics, including my colleagues and officemates back at Y Combinator Research where I worked in 2016-2017,59 some of whom were researching basic income, as well as others who were researching AI at OpenAI and Google Brain who came by sometimes. All these folks helped me develop nuanced perspectives on both UBI and AI, and an appreciation for the subtleties of their context and implementation.

I’d also like to acknowledge my supporters on Patreon,60 without whom I would not have had the space to develop my own skills and thinking, as well as all of my followers who have allowed me the hands-on experience of being a professional “influencer” and “content creator”. My perspective has been influenced by many thoughtful conversations with other professional content creators and their experiences working on the platforms of various tech giants.

I am currently doing research on AI, economics, and data as labor with the support of Microsoft. My opinions in this piece are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of my present or former employers or colleagues.

And finally, given that deep engagement with long-form content is rarely incentivized, thank you for reading! You could have been consuming and judging scores of photos or tweets, and your likes/shares/votes per minute has greatly suffered by you being here. The internet is not a one-person-one-vote system, and you give up short-term algorithmic influence when you spend time on an independent blog, but I promise you’ll be of more value to our future AI overlords if you judge less and learn more. Take care of yourself and see you next time!

- Vi Hart

References

- Turing’s original paper is called “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, and it is quite readable if you’re interested: https://www.csee.umbc.edu/courses/471/papers/turing.pdf

- He talks a little about the timeline in this interview: https://www.webofstories.com/play/marvin.minsky/136