Shown above: Social distance balloons. (The balloon on the left is a hologram, remoting in via augmented reality to share time and space with the physical balloon on the right.)

Our team has worked remotely for years, particularly using VR and AR. Using new tech for doing real work has pushed us to focus on what actually works for us when we’re working together, rather than staying attached to some idea of what remote collaboration should look like. We want to open up all the possibilities new technology can create, before it becomes standardized and invisible to us just as prior technology we use every day, from the phones in our pockets to electricity, plumbing, and transportation infrastructure.

But while VR can do more than real life in some ways, there’s still other things that in-person meetings are best at. So after years of working with Evelyn Eastmond earlier this year I finally took the opportunity to visit her and do an art residency at the Norfolk Art Residency, to focus on in-person work using physical materials.

Little did I know that during the weeks I was traveling on the East coast to visit Evelyn as well as other folks I usually meet with remotely, the tables would turn. COVID-19 started spreading rapidly in the US and folks who usually work in person were required to start working remotely!

As I had already been traveling for weeks, staying home wasn’t an option. We decided it was safer to go ahead with a proper art residency in her studio space than for me to fly home while airports were busy and precautions hadn’t yet been put in place (this was early to mid-March), and so while many of our colleagues made the shift to working remotely, Evelyn and I focused on what we could do on location in person. We hoped that our experience working remotely would help us highlight what in-person things can’t be replaced. I’ll try to write up some conclusions on that topic later in this post, but now it’s time for the art!

The intention was to have the freedom of a large open space to fill, and there’s two ways I know how to fill space quickly without too much waste or expense: one is balloons, and one is AR. So I did both together.

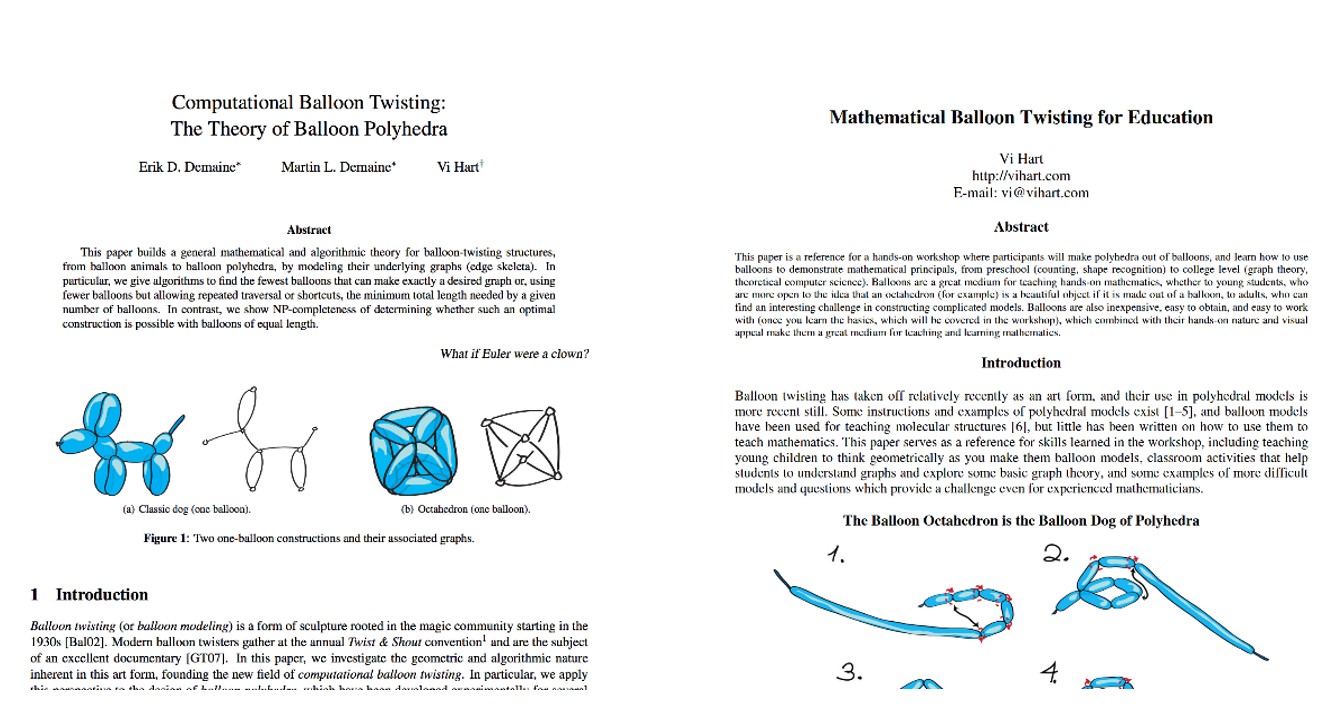

I started my balloon art journey a dozen years ago with mathematical and computational balloon twisting, exploring what was theoretically possible as well as optimal strategies for making geometric figures:

Back then I was a more traditionally academic mathematician (“more” being relative). I wouldn’t have known how to justify myself as a balloon artist unless everything were precise and mathematical, computationally efficient, and something you could publish papers about. Which I did.

This time around I wanted to explore balloons from a less rigid perspective. With the help of brilliant formally-trained artist colleagues like M Eifler and Evelyn Eastmond, I’ve grown as an artist in the past few years and have learned to embrace making art that feels right in ways I don’t know how to explain or justify with logic. And now I had a whole barn full of space and materials to work with, safe knowing that the computational aspect would come in via a mixed reality layer, “legitimizing” the work as technical work. This is how I fool myself in to being free to experiment with materials.

I was originally going to do a short residency, just for a few days while I happened to already be on the east coast. So I filled up the space with balloons the first day:

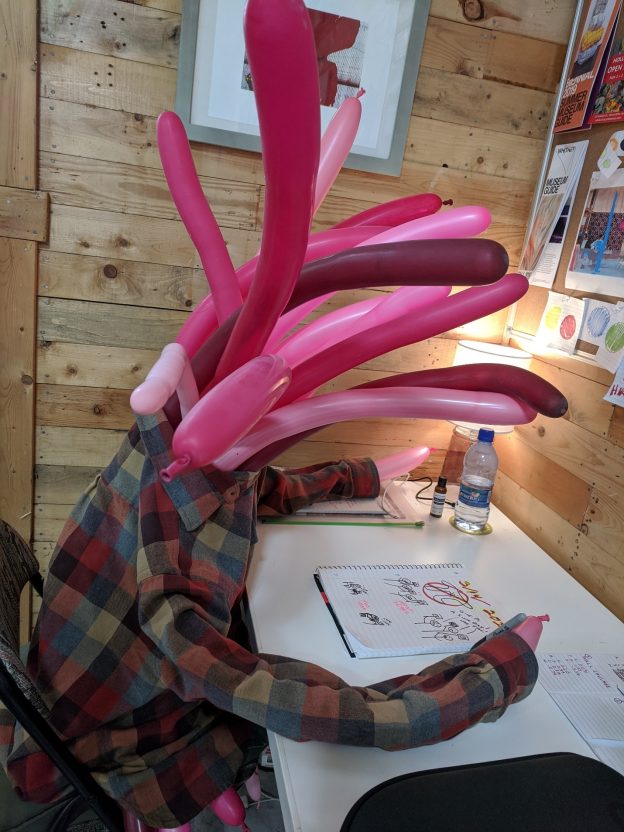

But as Covid-19 got a foothold in the US, I decided to delay my return flight to avoid the crowds. By the time I flew back airports were sparsely populated and everyone was being careful. I had the time to iterate and experiment, as well as spend a couple days on a side project PSA on the unfolding crisis. Here you can see my balloon-self hard at work on said side-project.

The Covid-19 reports started coming out and it became clear just how many cases were in the US and how ill-prepared we were for it. The balloon art project was meant to be delightfully ridiculous, but the crisis added a sharpness. It worked for me. It made it both more absurd and more serious. It was absurd that I was delighting in balloons during a pandemic, but also I also knew the situation was too big and too serious to understand the consequences all at once. I knew at that point that there was a not unlikely scenario where millions of people would die. I knew it was not unlikely that people I cared about would die. I knew the world would be forever changed, and that this wasn’t a matter of folks staying home for just a couple weeks and then things going back to normal. But what to do about it?

I felt the urge to DO something, but I didn’t want to jump in and make a mess of something I knew very little about. Short term, it seemed like of all the options, the one guaranteed to do no harm was to stay put and make art.

I had originally thought I might do some balloon twisting more reminiscent of what I’d done in the past, but in the end not a single balloon was twisted. I ended up incorporating more of the local materials in Evelyn’s barn, as well as using balloons that were deflated or broken. Such are the times.

My strength is in long-term integrated thinking, and it was useful to keep my hands and body focused on a physical task while my mind mulled. Part of me wanted to do something, and what that part of me wanted to do first was to panic-travel-home and panic-stock-up, then figure out how to magically save the economy. Part of me wanted to agonize with the decision of what was the best way to be spending my time, would I regret it if I did this or didn’t do that, what if I get stuck on the east coast, what if by the time I get home the stores are all shut down, I have no food at home because I’ve been travelling for weeks, is it better to fly home and then self-quarantine as soon as I’m home, or is it better not to fly home but be stuck traveling and unable to isolate?

These aren’t the questions I wanted to be focusing on. I figured they would become clear in a couple days whether I stressed about them or not. I wanted to be focused on bigger picture things, and I knew I couldn’t go wrong with staying put and making art. Big art for big problems.

We all process things differently, though I couldn’t say exactly what my process is. I found myself inventing a fictional process to retroactively explain my prior actions. I shared photos with M and Evelyn to show my progress as I created the correct length of balloon using a chop saw and achieved flat ends using a mallet.

I had a few art pieces that needed virtual components, so I called in help from Evelyn and M. Evelyn created a computational layer using MRTK and MRE that would synchronize objects in space between our HoloLens view in the barn in Massachusetts, and M’s view in Altspace in the Vive VR headset in San Francisco. M created virtual balloons of various personalities to join the physical ones, and they showed them to me from VR while I observed them in AR.

Years ago M and I shared an office in SF, while Evelyn remoted in. M and I would sometimes be in the same room physically but different rooms virtually, and sometimes even when we wanted to be in the same virtual room it was just more convenient to use separate physical spaces. Evelyn had to remote in more often, but we were so used to working virtually that I quickly lost track of who was physically present during which meetings. It just wasn’t important to our work.

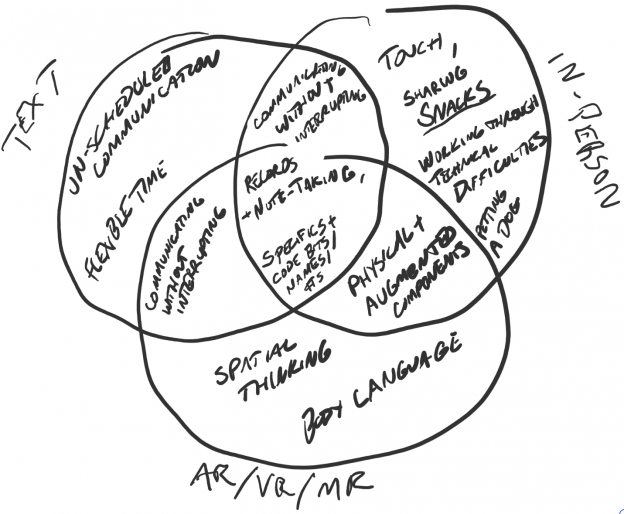

This time, Evelyn and I were at the same location, but still it was often more convenient for me to be in the barn in AR while Evelyn used VR from her house. Some of what we worked on was best done in the same room face-to-face, but sometimes it just created an unnecessary and distracting physical echo removed from the work we were focusing on. And as always, sometimes even when someone’s physically nearby it’s best to just send a chat message, especially where having the specific information written down helps, or when you don’t want to interrupt, or when it’s a to-do item for later.

All these modes of communication have their strengths. Spatial computation gives superpowers that analog life doesn’t have. Text communication has been around for long enough that we’ve developed tons of strategies to use it for record keeping, lists, increasing working memory, and to index and search key points. In-person communication still shines when it comes to working with physical materials, emotional material, or sharing food and drink, and the history and traditions we’ve built go much further back than text, but we’re also learning ways to work with materials, emotions, and even snacks, that play to remote collaboration’s strengths. The real place where in-person physicality shines is physical human touch, but even pre-pandemic, touch is less a priority to have available for work situations.

In our current prototype, VR users have a lot more control using the tracked hand controllers than the HoloLens viewer has, who can only click on things. So I stood with a birds-eye view of the space and directed M where to move each object to fit my vision. This interaction was in some ways novel (M showed up in the barn with an avatar that looks like Clippy), and in some ways very normal.

“A little to the left… no, your left… a little more… ok back a smidge… THERE!”

These meetings were done not only between myself in the hololens and M in the Vive, but with Evelyn at her computer making changes to the code as M and I tweaked the design, and with the three of us also in a voice, video, and text chat over Teams. Voice chat is the foundation, as there’s no integrated voice chat across these systems, and while different headsets do different things, voice chat is voice chat. It keeps the meeting continuous as we take on and off different headsets or turn on and off video. Video chat helps so that I can show the physical barn and we can see any important gestures not captured by the headsets, and it also makes silences extra comfortable as we can see that each other are working on our next tasks (moving something, coding something, designing something) and haven’t disappeared due to lost connection. Text lets us send the occasional name, parameter, or link. We’ve gotten fluent in layering these different technologies, though we weren’t perfect at it at first.

I’ll highlight three of the pieces in the final gallery show that include AR elements:

1: Centerpiece

The centerpiece of the gallery involved a number of large transparent balloons hanging at body-height, with room to walk between. I wanted these transparent objects to feel reminiscent of virtual objects, nearly weightless and lacking solidity. At least, that’s the concept I started with when I had ordered those balloons and planned the piece well ahead of time.

Once I started working on it in the context of world events, other feelings came out too. These larger balloons were inflated with my own breath, about 7 full breaths each. It’s not exactly easy to force the air out of my lungs and into these nonstandard balloons, and breath after breath you start to feel it. It’s work. I didn’t know much about Covid-19 at the time (no one did, we still don’t), but I did know that it is a virus that attacks the lungs, leaving many people gasping for air, needing ventilators that are in short supply. I was hyper-aware of my own breath as I struggled to inflate these balloons. Every time I saw this piece I saw my own breath inside those balloons, precious breaths given form, possibly infected with disease, invisible except for the pressure it exerts on what’s around it.

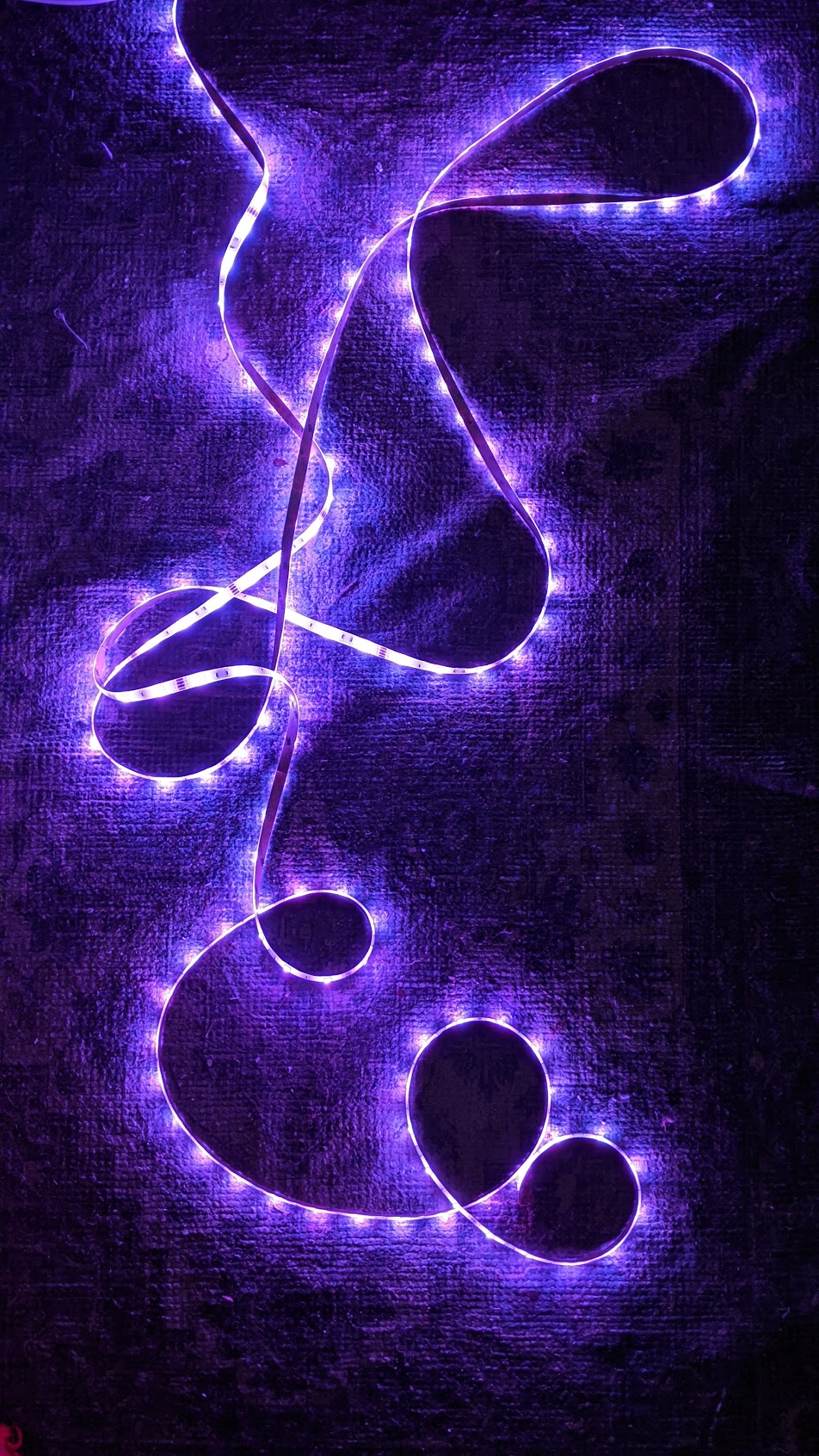

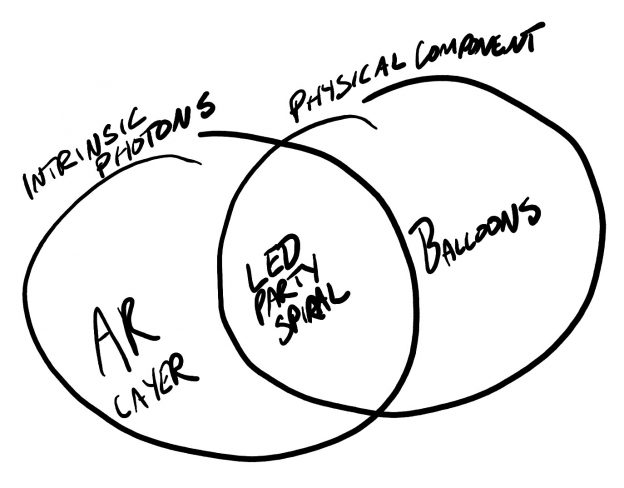

One of the balloons had a light strip spiraled around it and facing internally, giving the physical component of the piece some intrinsic photons, rather than relying only on external light to be visible. This piece’s AR component is made only of photons, so I think of that one balloon as bridging the gap between physical and photonic, as well as providing a strange party atmosphere.

The virtual component is a number of virtual balloons that look quite similar to their physical counterparts. When viewed through the HoloLens, it takes a moment to tell the physical and virtual apart. Walking through the piece requires identifying and walking through the virtual objects while avoiding the physical ones.

The final result ended up being even more compelling than I imagined it would be. It doesn’t photograph well because it is meant to be experienced, but it was a cool enough experience that I spent a lot of time wooshing around inside the piece.

An unexpected side-effect is that the physical balloons have a tendency to follow your wake, sucked in by the movement of the air. This would easily differentiate them from the static virtual balloons, except that they are behind you. An outside observer can easily see what is real and what is not, but from the inside perspective the consequence of your passage is invisible.

This led a joyful embodied component to the gallery opening party, of four people including myself, Evelyn, her partner, and their dog, all carefully scooting or dancing through the balloon environment 6 feet apart from each other.

2: Conversation

Without AR:

With AR:

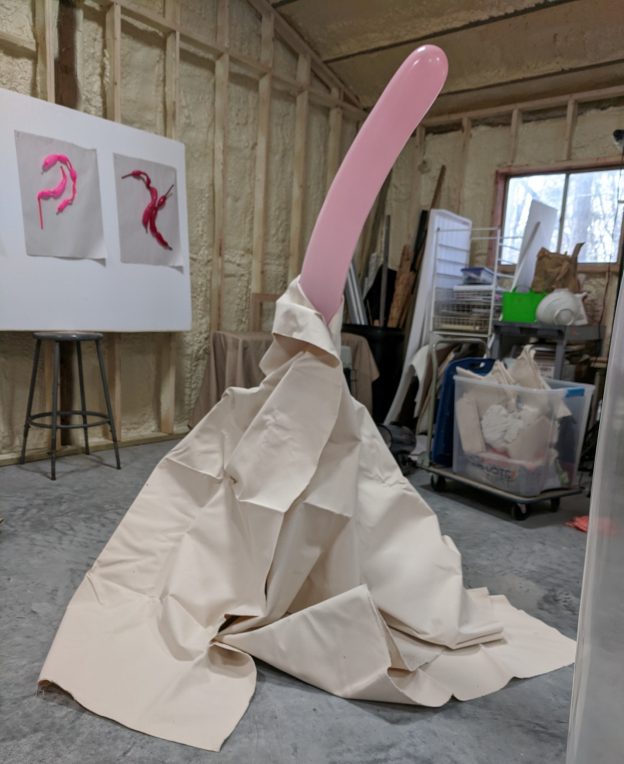

I used cloth extensively through this residency. Cloth often works symbolically as a light and free material, pliant and flexible, but alongside balloons and AR it becomes the most unyielding and weighty aspect.

Canvas, especially, becomes a sturdy and structured material when compared to balloons. It lends a certain gravitas to the discourse between these figures.

One visitor to the gallery compared them to the three Oracles of Delphi. I thought they might be the three Norns or three Fates. When there’s a pandemic, even a single balloon wrapped in a single piece of fabric can evoke the most serious of characters.

Because there are three figures in conversation, even without the AR headset the viewer understands that there is supposed to be a 3rd figure and can predict where it is and how it is postured. It invites one to join the conversation.

3: Social Distance Balloons

Ah, I forgot to mention the poking stick, so let me back up a little. The first version of the balloon figure reading a book looked like this:

We must avoid touching our faces to avoid becoming infected, and balloons also must not touch their own face. We also must avoid touching common surfaces, and so I created poking sticks so that visitors could touch all the art through a weird limp balloon finger.

When I saw the mask on Evelyn’s workshop table, I couldn’t resist borrowing it for my balloons. It started on a separate figure, while the original figure reading a book evolved to a comfortable livingroom scene between one physical and one virtual balloon reader.

Finally these merged into one focused piece. Between the mask and the remote visit, we can hope this balloon’s breath will hold.

Aftermath

The above was written in March, after I found my way home. It just needed the pictures added in. Instead I dug into COVID-19 research, collaborating with experts to work on policy recommendations which have had some impact.

Now it is late May, and I’ve been able to do everything I felt the urge to do during the art residency time but didn’t know how to do while ensuring a positive impact rather than adding more mess and noise to the crisis. The art residency gave me time to think bigger picture and art my way through some feelings, preparing me to be able to jump in effectively the moment the opportunity arose.

Meanwhile, my colleagues have taken our work on collaborative MR spaces to the next level, exploring use cases for quality remote education. I hope we’ll hear from them about that on this blog soon!

Thank you Evelyn for being an amazing host, and the Norfolk Art Residency for giving me the time and space for art. Here’s to greater appreciation of the things the world runs on that so often become as invisible to us as the air we breathe.